This December marks the end of my 30th year working in politics. That has led to some reflection, some of which I share here and on Medium.

Thirty years ago, Andy Gordon, the incoming chief of staff to incoming US Representative Sam Coppersmith, hired me to be Sam’s director of constituent services. After figuring out that one of my uncles was his classmate at Redlands High School, and another was his camp counselor, Andy said “If I’d known you were one of those damn Loge boys I never would have hired you.” To repay his confidence, I once stranded the Congressman in a purple 1974 Triumph Spitfire (years later when telling that story, Sam said I was “too pathetic to fire”).

Below is a self-indulgent glance at the years and a few of the lessons I’ve learned.

The years.

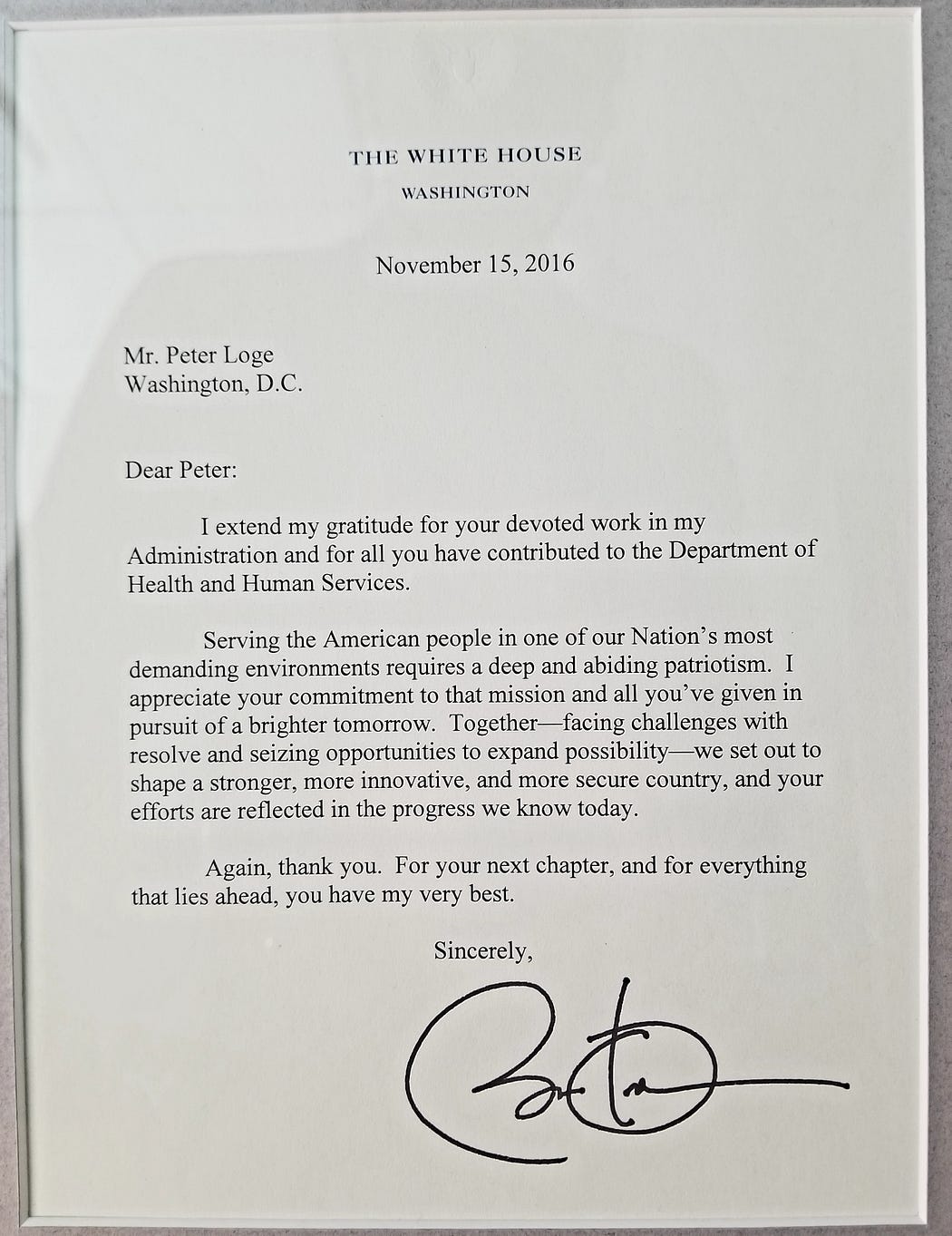

Over the past 30 years I have served in senior staff positions for Coppersmith, two other members of the US House (Brad Sherman of California and Steve Kagen, MD of Wisconsin) and US Senator Edward Kennedy. I was senior advisor to the Commissioner of the US Food and Drug Administration at the end of President Obama’s second term, served as vice president for external relations at the US Institute of Peace, was a senior vice president at a consulting firm, had my own firm for seven years, and more. I’ve led, helped lead, and advised organizations and campaigns big and small, some of which you’ve heard of, most of which you haven’t.

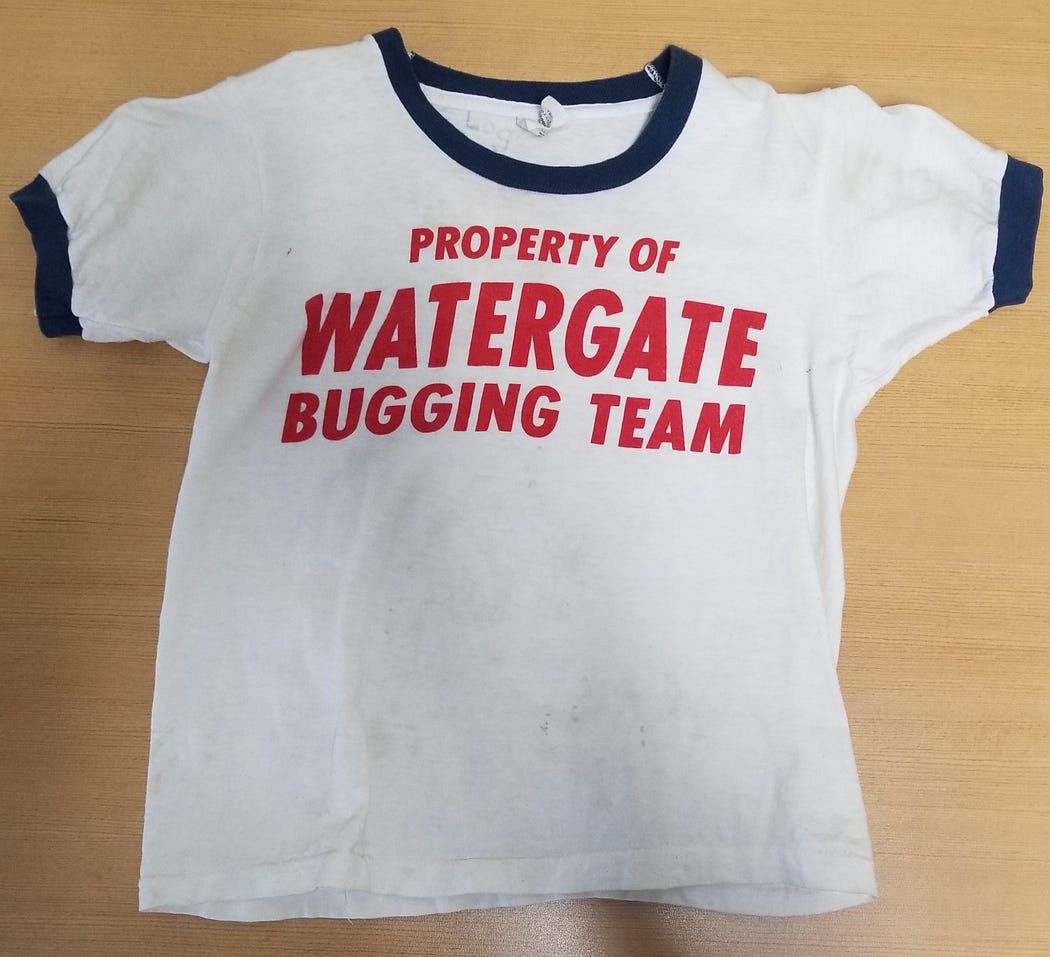

Over that time I worked on the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”), was a chief of staff in the House during Clinton’s impeachment, was at the White House a few hours after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School (for a Christmas party of all things), put the first member of Congress on the internet, ran an organization that helped re-define the death penalty in America, helped advance Senator Kennedy’s memorial at the US Capital, lobbied for America’s Funniest Home Videos, and more.

Since Andy hired me, I’ve attended four Presidential inaugurations, three Democratic National Conventions and countless fundraisers.

From 2000–2016 I was an adjunct instructor in the School of Media and Public Affairs at The George Washington University, spending 80% of my time on politics and 20% on teaching. Since 2017 I’ve been an associate professor (and more recently associate director) there, teaching 80% of the time and doing politics the other 20%.

I’m the political equivalent of a working actor, the guy you know from the thing. I’ve had central roles in a big issue or event or two and turn up in The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal from time to time, but I’m mostly in the supporting cast and am usually quoted in less widely read media.

The past thirty years have also had a few odd sidetracks. There was the brief turn as a sculptor, a handful of political satire commentaries on National Public Radio’s Morning Edition (the Washington Post once accused Saturday Night Live of stealing one of my ideas), and a book drawing lessons for managers and organizations from soccer. A friend named a character in a series of political thrillers after me (the fictional Peter Loge is more interesting than the real one), and last year a colleague and I started a strategic communication podcast.

My general rule of thumb is that I do stuff I find fun or interesting, as long as enough of it turns into money I’m happy. So far it’s worked.

The lessons.

It’s always dicey to draw lessons from one’s life, and dicier still to think those lessons should be shared (to say nothing of egotistical). Our world is big, chaotic and confusing. One way we make sense of it is through stories. We find patterns and reasons, we identify causes and consequences, we name heroes and villains, and then live the stories as if they were true. But the stories we tell are typically only casually connected to facts, they are true to life but rarely fully accurate. We make our lives make sense, regardless of the sense in them.

The lessons I assert I’ve learned, the wisdom I claim to have somehow accumulated, may be no more than the result of my current mood, what I read most recently, or what’s on my to-do list. This story helps me make sense of what I spent the last three decades doing, but that doesn’t mean it’s true.

A more practical problem with the story is that, even if true, it may not be relevant to anyone who isn’t me. My lessons are derived from the particular circumstances of my life. And of course, the political world in which I started volunteering as a kid is different than the one my students are entering. On the first campaign on which I volunteered, a mayoral race in my hometown of New Haven, Connecticut, I hand delivered press releases on my bicycle. Things are different now.

Nevertheless, here are six of the lessons that I have learned.

Be generous.

Give freely of your time, energy, and money. Say ‘yes’ when you can (and be honest when you can’t). If someone asks for coffee or a call to get career advice or run an idea by you, try to find the time. Your 30 minutes will matter more to them than it does to you. If a friend asks for a donation for their favorite cause, and you can afford it, chip in. It matters enough to them to ask, and they matter to you, so support your friend if you can.

In 1992 or 1993 several people in Tempe, Arizona encouraged me to run for the state legislature. The district was Republican, but with the right candidate and a bit of luck a Democrat might be able to pull it off. One of the people I called for advice was Chuck Blanchard, then a state senator from Phoenix. I barely knew Chuck and we ran in very different circles. He gladly met me for breakfast and we talked through what running might look like. There was nothing special about me, Chuck owed me nothing and I was unlikely ever to be in a position to help him. But he took time because he is the kind of person who returns calls, has coffees, and helps where he can regardless of who you are. (I opted not to run).

A more recent role model is the late Grant Wahl. Grant died while covering the FIFA men’s World Cup in Qatar. One reason his death shook the sports journalism and soccer worlds is because for as good a writer as Grant was, he was a better person. He was generous with his time, his attention and energy.

If people like Chuck and Grant can make time, I certainly can. You probably can too.

The person you help today may help you tomorrow, and the person you’re a jerk to today might remember it next time you need something. But that’s not why you should be generous. I’ve known Chuck for more than 30 years. Letting him stay at my house a couple times doesn’t begin to compensate him for all the help he has given me. Grant didn’t ask for or expect anything in return when he agreed to participate in an event I was hosting. Chuck and Grant’s generosity is about being in the world, not keeping score.

Hustle.

When I was starting my consulting firm, a friend pointed out, “success is hard, if it were easy everyone would be successful.”

The most professionally successful people I know work hard. They make calls, look for opportunities, and keep getting better at what they do. They work to prove their worth and earn their keep every day. They know the world is full of smart, hard working people, all of whom also want to be successful. They know that what matters isn’t what you did last, but what you’re doing now and what you’re going to do next. They hustle.

There are people for whom the phone rings a lot. I’m not one of those people. I have been most professionally frustrated when I expected someone to reach out and offer me a box of money in exchange for my wit and wisdom, or because of some unique quality I would like to imagine I possess. I’ve seen frustrated friends in similar positions who think “don’t they know who I am or what I’ve done?” The phone sometimes rings, I’ve gotten some lucky calls, but not often. Waiting rarely results in success.

I don’t mean the “win at all cost my worth is measured by how tired I say I am and how hard I appear to be working.” This version of hustle culture was taking a deserved hit before COVID, and the pandemic may have largely done it in. I mean the kind of hustle that recognizes that you have to earn your next job or client. Hustle means finding and making opportunities. It means learning a new skill, sending another email, trying another angle.

Be present.

One problem with hustle is that you’re always working for the next thing. That means you’re never fully where you are. Endless striving is the worst application of Zeno’s paradox, always one gig away from happiness.

The point of your current job isn’t just your next job, it’s what you’re doing now. Do what you’re doing, be where you are. You don’t always need to hop to the next rock. You can say “this is where I am and where I want to be.”

A popular parable tells a story of an investor and a fisherman. An investor on vacation in a small beach town sees a man row out to sea every morning and come home every afternoon with fish he sells in the market. The fish he doesn’t sell he grills over a fire on the beach while he sips a beer and watches the sun go down. After a few days of this, the investor approaches the fisherman and says “I can help.” “Thank you,” says the fisherman, “help with what?” “Your fishing.” “That’s very nice of you, how?” “I’m an investor, I can help you buy a bigger boat, or even a fleet.” “Interesting, but how does that help?” “You could build a business and sell a lot more fish to a lot more markets.” “How is that helpful?” “You’d get rich, you could do anything you wanted. If you had all the money in the world, what you do?” The fisherman paused. “Probably buy a little place on the beach, go fishing every day and at night sit by a fire and watch the sun go down.” (Paulo Coelho’s version is here).

I’m not great at this. Most of my life has been about hustling. Since I was about 12 I’ve worked in a record store, at a newsstand, in a restaurant, as an office temp, and more. I’ve sold magazines over the phone and politics door to door. I started my first company as a teenager. Hustling is what I do, I have to work to make it not who I am.

A few years ago, I’d checked all the success boxes I was likely to check. Senior political positions: check. Working on big deal issues: check. Showing up in the media: check. Financial security: check. I’m not going to build a big firm, get rich, or be a cabinet secretary, and that’s fine. I teach some classes, advise some clients, pursue some ideas, watch the sun go down. I’ve got my metaphorical house on the beach. Yet there’s a part of me (somedays a big part, some days a small part, but always a part) that says “keep moving, what’s next?” A lifetime of chasing makes it difficult to have arrived.

Give it a shot.

When I was younger my dad gave me some advice that, in the moment, sounded terrible and mean. He said, “the worst you can do is fail.” But if you think about it, failing usually isn’t so bad.

A bunch of years ago I had what I thought was a brilliant idea for a sardonic, Raymond Chandler-talking, fedora wearing, old-school lobbyist who revealed the real workings of Congress, good and bad. He would become a political cult figure, his identity secret and his insights spot-on. Insiders would leak information to the fictional character and hope to turn up in his musings. I recruited a couple friends to help, set up some social media accounts, and started writing my best political noir. Apparently I was the only one who thought it was a good idea. Which is to say, I failed. So? I lost some time and had some fun. Moving on.

On the other hand, I fully committed to writing a book about lessons managers and organizations could learn from soccer. I’m a mediocre pickup player, had never written a book, and have never taken a management class. With a lot of help and a lot of luck, Soccer Thinking for Management Success debuted as a #1 new release on Amazon.

If the worst you can do is fail, you may as well give it a shot.

Luck matters.

My standard reply to the question about how I got to where I am is “dumb luck and minor tactical errors.” I grew up in politics, but stopped after college to try to become an academic. In 1991, I was teaching public speaking at Arizona State University while in the political science graduate program. I started every class talking about the news of the day, which then included Jerry Brown making a somewhat quixotic run for the Democratic nomination for president. I felt bad about all the flack I was giving his campaign, so called his 800 number (a big deal in 1991), never heard anything, so kept poking fun at the campaign. I eventually heard from them, asking if I would run as a Brown delegate to the 1992 Democratic convention. “Sure, that could be fun.” I called the Arizona Democratic Party to find out who was in charge of his campaign in the state, we met for coffee, and she asked me to be a state director. From there I ran a state legislative race (we lost) but Sam Coppersmith, whose Congressional district included my candidate’s state legislative district, won. Then Andy Gordon called. The past 30 years of my life have been the result of a series of jokes about Jerry Brown.

My career is littered with luck. I work reasonably hard and consider myself reasonably smart, but those are table stakes in DC. A lot of people work a lot harder and are a lot smarter than I am. As much as I would like to think I am where I am (wherever that is) because of my insight, wit and brilliance, the reality is closer to chance.

Not all the luck has been good. I’ve missed events and calls, come in second for jobs, been just a bit off on timing. Once I didn’t get a position because the White House called on behalf of another last minute candidate, not a lot I can do about that. But overall I have been absurdly, unreasonably lucky.

Everyone is doing the best they can.

The biggest lesson I’ve learned over 30 years is that everyone is doing the best they can. There’s no moment when everything suddenly makes sense. No secret government agency hands you the codes to being an adult or slips you the answer sheet in a parking garage. Everyone is more or less making it up as they go and hoping for the best.

Students often sit in my office at GW distressed that after four years and an obscene amount of money, they’re not sure what comes next. They’re worried they might take a wrong turn or somehow miss the exit clearly marked “Adult.” As gently as I can I try to explain that no one has any idea what they’re doing, that all of my friends have the same questions they do. Some students find this liberating, many do not.

Years have brought perspective. I’ve honed some useful skills, and I do some things more quickly and a bit better than others without my experience. I’ve accumulated a fair amount of random bits of information that help students and clients. I see connections where others may not because I’ve spent a career connecting things. I know a lot of people, which helps in my business.

But in many ways, to quote Han Solo, “it’s all a lot of simple tricks and nonsense.” A nice thing about age is that I’m OK with that.

There are probably more lessons and insights (be kind, be interesting, get over yourself, be curious, never stop learning, the list goes on) but this is overly self-indulgent and too long already.

After 30 years of working in politics I’m a bit more patient, a bit kinder, a little less convinced of my own specialness than I was when Andy Gordon hired me (and Sam Coppersmith later didn’t fire me). I keep trying to get and be better, keep trying to follow my own advice. Some days it works better than others. Like everyone else I’m just doing the best I can.

All in all it’s been a heck of a run, hopefully one I can continue a little longer.