Also posted on Medium.

On November 1 I was honored to speak at a University of Connecticut POLS Colloquium. Below are my remarks, as written. As delivered they included a pretty good Columbo impersonation and a few other asides, but this is pretty close to what I said.

Thank you for inviting me to join you today for what I hope will be an interesting conversation. My name is Peter Loge. I’m an Associate Professor in the School of Media and Public Affairs at The George Washington University, a strategic consultant, and most recently the author of a book called Soccer Thinking for Management Success: Lessons for organizations from the world’s game. I mention this last bit in part to explain why I will do all I can to make my flight back to DC tonight and be in my seat at Audi Field, papusa in hand, by the 8:08pm kickoff of DC United’s playoff game against the Columbus Crew.

My position is not a tenured one — I have a couple of Masters degrees, but I quit the PhD program that Professor Morrell finished. For the past two-plus decades I have worked in and around the federal government. I have served in senior positions in the House, Senate, and Obama administration, I’ve run and helped run advocacy, non-profit, for-profit, and quasi-governmental organizations, have lobbied, designed and managed issue and candidate campaigns, and have otherwise carved out a reasonably successful and really lucky life in the swamp. I was also an adjunct instructor in the School of Media and Public Affairs at GW for many years before joining the faculty fulltime last fall, and have taught at Emerson College, Clemson University, Arizona State University, and elsewhere.

Theory has always been the foundation of my courses.Protagoras is a staple in my political communication classes in part to raise ethics issues early, and in part to make juniors and seniors who have spent a couple hundred grand studying the art of politics uncomfortable about most of their career, if not their life, choices. My students have come to expect rants, good and bad, about George Lakoff, Jean Baudrillard, and others and I am overly fond of saying “it’s all warmed-over Aristotle.” The question of political communication ethics is usually part of other conversations, and occasionally it’s an exam question. We talk about Protagoras, argue about the implications of Nietzsche on language and whether or not Rorty offers a way out from the despair. But my job is mostly the practice of theory, not the theory of practice.

Today’s talk is part of a larger project that I hope will turn class mentions and occasional essays into focused and serious teaching and research on ethics in political communication.

The mid-20th Century rhetorical scholar and conservative public intellectual Richard Weaver lamented that “in the not-so-distant Nineteenth Century, to be a professor of rhetoric, one had to be somebody.” Tragically in the view of Weaver, “Beginners, part-time teachers, graduate students, faculty wives, and various fringe people, are now the instructional staff of an art which was once supposed to require outstanding gifts and mature experience.” (Language is Sermonic). As someone who assigned this reading from Weaver when I was an adjunct instructor and whose wife was for a time on the Board of Trustees at GW — making me both a part time teacher and a faculty spouse — I’ve always had a soft spot for Weaver’s lament.

Weaver’s complaint is not a new one. In about 95 C.E. the great Roman orator Quintilian wrote, “…for a considerable time the instructors of morals and of eloquence were identical.” (Institutio Oratoria, Book 12, Chapter 2). Quintilian further writes, “For as soon as the tongue began to offer a way of making a living, and the practice developed of making a bad use of good gifts of eloquence, those who were counted able speakers abandoned moral concerns and these [moral concerns], left to themselves, became as it were the prey of weaker minds.” (quoted by Arthur Walzer in“Moral Philosophy and Rhetoric in the Institutes: Quintilian on Honor and Expediency”).

For Weaver, rhetoric is “truth plus its artful presentation…” He goes on to write that “rhetoric at its truest seeks to perfect men by showing them better versions of themselves, links that chain extending up toward the ideal, which only the intellect can apprehend and only the soul have affection for.” (The Ethics of Rhetoric) Weaver, like Plato, argues that rhetoric is, or ought to be, about the nature of the good. Such a claim assumes that there is a good, that it is knowable, and that it can be communicated (or drawn out, depending on how Platonic you’re feeling). But if there is no universal good, if there is a universal good but we really ought not talk about it while we’re still up for tenure, or if there is a universal good but we can’t comprehend it or communicate it even if we could comprehend it, then it seems easy to just teach, as Phaedrus conceded the sophists teach, “not what is really right, but what is likely to seem right in the eyes of the mass of people who are going to pass judgment: not what is really good or fine but what will seem so…” Or as Socrates helpfully rephrased it, “a method of influencing men’s minds by means of words.” (Phaedrus — it is worth noting the above from Weaver is from a chapter titled “Phaedrus and the Nature of Rhetoric”).

But if rhetoric is removed from fields devoted to the study and teaching of the public good, public discourse, and persuasion with a civic or civil purpose, we risk becoming Plato’s parody of the sophists. Absent a foundation in The Good, or at least a nod to a good, rhetoric becomes the worst kind of public relations, something the clever do on behalf of the smart. It is “making bad use of good gifts.”

How did we get here? I blame Harvard. More precisely, I accept that a piece in the July-August 1995 issue of Harvard Magazine called “How Harvard Destroyed Rhetoric” is accurate. The piece was written by Jay Heinrichs, who was the editor of the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine at the time. Do with that credential what you will. Heinrichs points out that Harvard’s first Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory was John Quincy Adams, who taught courses while serving in the US Senate –which is to say he was a part-time teacher. Over time oratory in the service of public debate gave way to oratory in the service of enjoyment or enlightenment. The Professorship is now held by Pulitzer Prize winning poet Jorie Graham. She replaced Seamus Heaney, a poet and Nobel laureate in literature. He replaced poet Robert Fitzgerald. And so on. Plato may have set rhetoric against philosophy, but at least they were in the same conversation. Harvard separated rhetoric from philosophy entirely.

Plato started the debate about whether or not one could both be a philosopher and a rhetorician, two thousand years later that debate is over and Plato appears to have won. We need to demand a rematch.

We need to teach political communication ethics because, in the words of Lee Pelton, the president of Emerson College, my alma mater, “the world is still in want of clear headed citizens, tempered by historical perspective, disciplined by rational thinking and moral compass, who speak well and write plainly.” Not for nothing, President Pelton earned his PhD in English from Harvard with a focus on 19th Century British prose and poetry.

Teaching ethics in political communication is tricky. It’s easy to agree with Weaver that rhetoric ought to be taken seriously because what we say matters and ought to be tied to greater ethical Good both because the Good is Good, and also because it is necessarily more persuasive because it is Good — even the sophist Protagoras would agree with the last point. It’s tougher to point to The Good, the ethical foundation, of which rhetoric is a part. If we were down the road-ish at Fairfield University this would be easy: we’d debate all semester, and in the end the Jesuits would win. But we’re not, and the Jesuits might be wrong. The Koran might have the last word, or the Torah, the Ashem Vohu, or the Ramayana. What if Nietzsche had it right that truth is a “mobile army of metaphor, metonymy, and anthropomorphism” or worse what if Baudrillard was right and we’re all just tourists lost in the desert of the real?

A pretty good description of the program in which I teach, the School of Media and Public Affairs at The George Washington University, comes from Protagoras in Plato’s dialogue of the same name. Socrates’ young friend Hippocrates was excited that the sophist Protagoras was in town, and was eager to study under him. But when pressed about precisely what Protagoras taught, Hippocrates couldn’t come with an answer beyond Protagoras being someone who “knows wise things.” This seriously troubles Socrates because “knowledge is food of the soul” and when the “soul is in question” one can’t be too careful. So Socrates helpfully agrees to scout the situation out for his young friend, and they head off to meet the sophist. Doing his best Peter Falk as Colombo impersonation, Socrates then asks Protagoras the same set of questions he asked Hippocrates. Protagoras tells Hippocrates, “the very day you join me, you will go home a better man, and the same the next day. Each day you will make progress towards a better state.” Socrates presses on Hippocrates behalf — better at what? If Hippocrates studied under a painter he’d get better at painting, if he studied under a flautist he’d get better at playing the flute, if he studies under a sophist what will he get better at? This is the important bit:

Protagoras: What is the subject? The proper care of his personal affairs, so that he may best manage his own household, and also of the State’s affairs, so as to become a real power in the city, both as speaker and man of action.

Socrates: …I take you to be describing the art of politics, and promising to make men good citizens.

Protagoras: That…is exactly what I profess to do.

Socrates: …I did not think this was something that could be taught.

Protagoras’s claim is UConn’s claim, or at least used to be UConn’s claim. The 1943/44 bulletin, the oldest on *the school’s website, defines the purpose of the University as including:

- The College of Arts and Sciences is designed to provide a broad foundation which will equip its students for further specialization or for immediate entrance into adult life and citizenship…

- [The University] is concerned with the all-around development of its students, and, to this end, it provides for their intellectual, physical, social, spiritual, ethical and emotional well-being.

- In its human relations the University seeks to increase the freedom which true education fosters.

Before you dismiss the standards and policies of the 1940s entirely, you should know that the same Bulletin estimated that tuition, room, board, books, and incidental university expenses for in-state students was between $460 and $550 a year. In a footnote the Bulletin noted that “Ten dollars should be added to these figures in the case of women students,” so not all good, but still, $500 a year in state. Just saying.

Consistent with the mission of the University, if not the cost, the current mission of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, “is to create and disseminate knowledge in the natural, physical, and social sciences and the humanities, and to help students acquire the skills and knowledge to become independent thinkers, lifelong learners, and responsible citizens.” Drifting from the 1944 mission, but responsible citizenship is still there.

The Political Science Department’s website says: Political Science serves students whose primary interest is in some phase of public affairs (law, politics, government service) or international relations (foreign service), in gaining a better understanding of the entire field of governmental organization and functions.

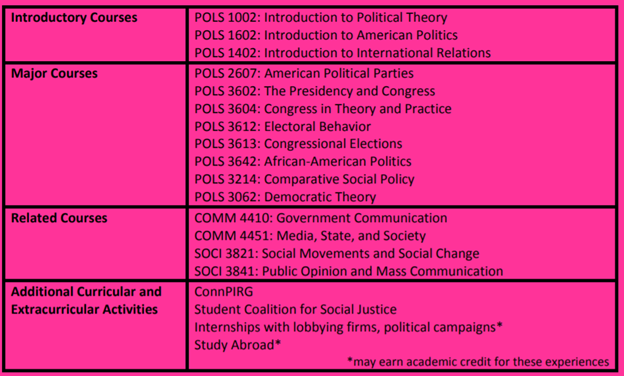

Citizenship and ethics are implied, and presumably discussed, but notably absent. This absence matters in part because the Center for Career Development points out that “political consulting” is a popular field for UConn poli sci alumni, and suggests the following curriculum:

I applaud UConn for training political consultants. One could make a reasonable case that the field of political consulting — the field in which I have spent most of my career and that many of my students go in to — was founded by the sophists. In the introduction to their 2003 book, The Greek SophistsJohn Dillon and Tania Gergel wrote that the “fees quoted for a full course from Protagoras or Gorgias [was] 100 minea (upwards of £100,000 or $160,000 in today’s prices).” That’s roughly a $15,000/month retainer, which is what a lot of lobbying and strategic consulting firms charge their basic clients.

But in lining up how we used to train people to succeed in public affairs, and how we now teach them, you can begin to see what I’m getting at. It’s not that UConn hasn’t moved on from a troubled past into a better future. Some of what UConn did in the 1940s shouldn’t have ever made it that far — for example, the University didn’t hire its first fulltime African American professor until 1957. But some of what has been lost is worth finding ways to reintegrate into research and teaching. It is time to re-engage the debate about the connections between rhetoric and philosophy, between political communication and ethics.

I hate the phrase “now more than ever.” By definition, the moment it the phrase is read it is wrong, because it is read after it is written, making it “then more than ever” with “then” being whenever it was the author first thought about dropping the cliché into the document. But there does seem to be some urgency to find ways to reunite civic and political education, citizenship, ethics, and politics.

Political rhetoric has become, in Orwell’s words, “designed to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind” in part because he have cut it adrift from its moorings.

I’m with Aristotle that rhetoric is not political science, but rhetoric is important to the practice of politics. In the Rhetoric Aristotle explains, “Ethical studies may fairly be called political; and for this reason rhetoric masquerades as political science, and the professors of it as political experts — sometimes from want of education, sometimes from ostentation, sometimes owing to other human failings.” For Aristotle, deliberative rhetoric is speech arguing about the best way forward into an uncertain future, which is to say it is political communication.

For the sophists, those great political consultants of yore, there may be an ultimate good but we can’t know it, so we have to find the best way forward we can, and the best way to do that is through deliberation. Those who would engage public debate should learn how to construct and deliver arguments. Through eloquence and deliberation the best path will emerge. For Protagoras, for whom “man is the measure of all things,” this is the art of politics. The somewhat more notorious Gorgias was also somewhat more cynical. In a philosophically prescient piece he may have argued that nothing exists, even if it did exist man couldn’t apprehend it, and even if he could apprehend it he couldn’t express it. All we have is how we talk about things. That talk, therefore, should be good. There are two great asides about Gorgias. The first is that he is reported to have had a gold statue of himself put in the town square, which feels very 2018, and when asked the secret to a long life — he died at 108 — he said he never let himself get dragged to other people’s parties.

Rhetoric went to poetry and speech departments. Speech became communications, and for undergraduates, it mostly means film or television, public relations or marketing, or similar degrees that teach people to present cleverly what other, smarter, people come up with. Philosophy went deep into philosophy, and with the exception of a handful of people like Richard Rorty — who abandoned philosophy in favor of poetry — it is largely absent from day to day politics. Political scientists study how politics works and how political systems work, but by and large leave questions of “ought” and “how to” to others. The exception at UConn may be your president, who studied political science and earned a PhD in communication theory. Mike Morrell comes close in his study of public discourse — how we can or ought to go about talking to each other in the public square.

Over in the Communications Department it’s much the same. A lot of people who seem smart and dedicated, but not a rhetorical scholar or ethicist in the bunch. One course description in the major lists ‘responsibilities’ once — and tellingly it’s a course on communication law, not persuasion or campaigns. Individual professors may talk about ethics in individual classes, but ethics are not a core feature of classes that future politicians and political consultants may take.

The policy program similarly offers nothing obvious in the way of ethics. The philosophy department has faculty who teach philosophy and language, but precious little that would encroach on either rhetoric or politics. Indeed, the word “rhetoric” doesn’t appear to appear in UConn’s course catalogs outside of the English department and courses on “rhetoric and composition.”

I don’t just mean to pick on UConn. You at least offer courses in politics and ethics. Southern Connecticut State appears to offer no courses in what could be called communication ethics or political ethics. UMass has one grad class in public administration responsibility. Quinnipiac offers majors in Public Relations, Advertising and Integrated Communications, and Communication and Media Studies but apparently no courses in ethics in any of them. Central Connecticut State offers a BA in Strategic Communication with no offerings in ethics. One localish exception is, predictably, Fairfield University which in addition to offering several applied and communication ethics courses requires those getting a degree in public relations to take an ethics course. This isn’t just a Connecticut and Western Mass thing. A study published in the journal Communication Education in 2015 found that only 51% of institutions that responded to a survey about communication ethics reported offering optional or required courses in communication ethics, broadly defined. The article, which updates similar earlier research, references media ethics, journalism, advertising, small group communication, interpersonal communication, and other important sub-fields — but not political communication.

As evidence that I am willing to bite every hand that feeds me, the School of Media and Public Affairs at GW, a program which has produced one of President Obama’s top speechwriters, the only speechwriter Senator Marco Rubio has ever had, Beto O’Rourke’s communications director, the communications director for Republican Representative Carlos Curbelo, Facebook’s first hire in DC, and many many more, has offered one course in political communication ethics, once. It was taught by me, last spring.

Some people who graduate from college go into politics. An increasing number start college with a career in politics in mind. Many of those students major in political science, and learn how our system was formed and how it operates. They may learn theories of representation, and the relative merits of different approaches to managing who gets stuff. Along the way they may take courses in public relations or strategic communication to pick up some skills they think they will need. But universities that sometimes don’t trust students to have the fortitude to listen to a speaker with whom they disagree or a topic that makes them uncomfortable assume that these same students will intuitively connect Rawls and Instagram, will find a Tocquevillean critique of Twitter too obvious to even bother discussing, or find a discussion of Rousseau and Facebook banal. We then wonder why young political operatives seem to have no ethical mooring, or are surprised when they insist that disagreement is somehow ignoble or worse. Argument is at the heart of politics, that’s sort of the point of politics. But we don’t teach our students that the point of political argument is to find the best path forward and then how to engage in those arguments. That means we don’t teach them that the path forward is about something greater than the win in the moment, that there is more at stake than the next election, numbers of clicks, or owning the libs. We don’t teach them that, in Weaver’s words, “ideas have consequences.”

The problem is getting worse. Rather than “now more than ever” or “a couple of weeks ago when I started drafting this than ever and then a bit more so on Monday when I was editing this while proctoring a midterm” we’re in the position of “soon more than ever,” we need to re-energize the study of political communication ethics and reintegrate ethics in political communication into the curriculum.

Politics is increasingly professionalized. We are awash in lobbyists, digital strategists, strategic communication consultants, speechwriters, professional community organizers, direct mail firms, TV and radio production houses, and fundraisers who pay for all of it and more. There are legislative staff, White House staff, governmental and quasi-governmental agencies, trade associations, non-profit and advocacy organizations, think tanks, and much more. The political industrial complex can be fun, exciting, important, and while only a few get rich most do well enough to at least spend some time advocating for what might broadly be called the public good. These professionals are graduating from UConn, UMass, Southern Connecticut, Harvard, Fairfield, Emerson, GW, and just about everywhere else.

Colleges and universities are both responding to and feeding this demand. More and more academics are studying political communication, more and more professors are teaching courses in it, and more and more students are learning it.

The George Washington University claims to be the first school to offer a degree in political communication in 1982. I will assert that Emerson College was second in 1986 — my degree, which I received in 1987, is a BS in Speech with a focus on Communication, Politics, and Law. According to the Princeton Review, 10 colleges now offer a degree in political communication, though I’m certain that’s an underestimate. The number goes up if you count graduate programs — many of which are basically technical schools for political hacks. More and more schools offer courses in speech writing, strategic communication, political advertising, and so on. But if you google “political communication ethics syllabus” an alarming number of results are my class. That’s not good news. The person who edited the book called Political Communication Ethics, Professor Robert Denton at Virginia Tech, is retiring. Again, not good news.

It is time that political communication followed business, journalism, medicine, and public relations, in making ethics a “thing.”

As the business of business became more complex, programs in teaching business emerged. The first MBA was offered in 1908 by Harvard. The Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at the time was an English teacher named LaBarron Russell Briggs. Briggs went on to become the Dean of Men and helped launch student services as something universities provided. One story goes that a Harvard undergraduate, having knocked a Yale student unconscious late at night after a football game, rushed to Briggs’ home and declared, “Dean Briggs, I’ve killed a Yale man in the Yard.” Briggs replied, “Why bother me at this time of night? Come to the office Monday morning and collect the customary bounty.” The bit about Briggs isn’t really relevant, I just think it’s a funny story and a bit telling about the status of rhetoric in 1908.

As it became clear that left to their own devices business leaders might not always make ethically sound decisions, schools began to teach business ethics. According to the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University, the first business ethics courses were widely offered by the 1960s, and the term “business ethics” entered common parlance in the 1970s.

We should do for political communication what others have done for business. Those who want to go into fields that are primarily talking about politics — running for office, speech writing, ads, campaigning, lobbying, and so forth — should have to take courses in political communication ethics. Courses in speech writing, campaigning, advocacy, and so forth should include at least one session on ethics.

Academics should probe the question of political communication ethics. Can there be a political communication “ethic” in the United States absent a shared external understanding of the Good? If so, to what should ethics be tied? Is this a moment to unite Rorty, Bellah, and Gorski with Aristotle? Can we accept Weaver’s admonitions but leave his politics on the curb? Or should we adopt his politics as well? What are the electoral implications of “ethical” campaigning? What is the relationship between norms and ethics? Do those who run on or with “pro-norm” messaging do better or worse than those who do not? Where and how do voters learn political norms? What do they count as ethical? Is there a gap between what academics think about ethics and how ethics are practiced? What do we do about that?

The word “rhetoric” might have fled the political stage for the relative safety and relative anonymity of poetry. But the original function of rhetoric — be it the “art of discovering all of the available means of persuasion in a given situation” (Aristotle), “good men speaking well” (Quintilian), or Weaver’s higher good — remains. We talk about politics, and politics is our talk. We debate and vote instead of beating each other up, or at least that’s how it’s supposed to work. Ethics may have fled with rhetoric, but instead of hiding out with poetry it appears to have stopped in a local bar, and stayed there. Ethics is the kid rhetoric left at a rest-stop saying he’d be right back.

It is past time to reintegrate ethics and rhetoric, and rhetoric and politics. If our political communication seems grounded in pure wind that may be because those of us who taught those doing the political communication never suggested it should, or even could be otherwise. We should fix that.